Wednesday, October 31, 2007

The Value of Continual Learning

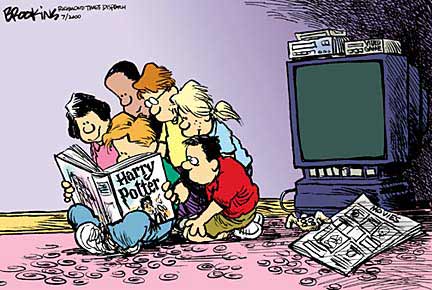

Fresh from another podcast hosted by the inimitable Siggy, he who puts me at ease and makes me think and reminds me why I wanted to be a teacher in the first place, I was reminded of this essay by Leo Buscaglia, from his book Papa, My Father.I wonder if perhaps one reason so many families view their children's school with suspicion these days is that parents no longer sit down with the kids at dinner and ask questions about their day. Getting a child's impression of a lesson while running frantically back and forth and trying to juggle schedules, and when the parent is dog-tired and unable to properly process information, can give a parent an impression that is completely inaccurate. Our society's inclination to find offense in just about everything also comes into play.

Perhaps if we took the time to actually listen to our children, we might discover that the world isn't really out to get us, so we might as well chill a little and let our children learn things we didn't already know.

I love this little piece of writing. Funny, how there is so much power in just a few words.

==

Papa the Teacher, by Leo Buscaglia

Papa had natural wisdom. He wasn't educated in the formal sense. When he was growing up at the turn of the century in a very small village in rural northern Italy, education was for the rich. Papa was the son of a dirt-poor farmer. He used to tell us that he never remembered a single day of his life when he wasn't working. The concept of doing nothing was never a part of his life. In fact, he couldn't fathom it. How could one do nothing?

He was taken from school when he was in the fifth grade, over the protestations of his teacher and the village priest, both of whom saw him as a young person with great potential for formal learning. Papa went to work in a factory in a nearby village, the very same village where, years later, he met Mama.

For Papa, the world became his school. He was interested in everything. He read all the books, magazines, and newspapers he could lay his hands on. He loved to gather with people and listen to the town elders and learn about "the world beyond" this tiny, insular region that was home to generations of Buscaglias before him. Papa's great respect for learning and his sense of wonder about the outside world were carried across the sea with him and later passed on to his family. He was determined that none of his children would be denied an education if he could help it.

Papa believed that the greatest sin of which we were capable was to go to bed at night as ignorant as we had been when we awakened that day. The credo was repeated so often that none of us could fail to be affected by it. "There is so much to learn," he'd remind us. "Though we're born stupid, only the stupid remain that way." To ensure that none of his children ever fell into the trap of complacency, he insisted that we learn at least one new thing each day. He felt that there could be no fact too insignificant, that each bit of learning made us more of a person and insured us against boredom and stagnation.

So Papa devised a ritual. Since dinnertime was family time and everyone came to dinner unless they were dying of malaria, it seemed the perfect forum for sharing what new things we had learned that day. Of course, as children we thought this was perfectly crazy. There was no doubt, when we compared such paternal concerns with other children's fathers, Papa was weird.

It would never have occurred to us to deny Papa a request. So when my brother and sisters and I congregated in the bathroom to clean up for dinner, the inevitable question was, "What did you learn today?" If the answer was "Nothing," we didn't dare sit at the table without first finding a fact in our much-used encyclopedia. "The population of Nepal is. . . ," etc.

Now, thoroughly clean and armed with our fact for the day, we were ready for dinner. I can still see the table piled high with mountains of food. So large were the mounds of pasta that as a boy I was often unable to see my sister sitting across from me. (The pungent aromas were such that, over a half century later, even in memory, they cause me to salivate.)

Dinner was a noisy time of clattering dishes and endless activity. It was also a time to review the activities of the day. Our animated conversations were always conducted in Piedmontese dialect since Mama didn't speak English. The events we recounted, no matter how insignificant, were never taken lightly. Mama and Papa always listened carefully and were ready with some comment, often profound and analytical, always right to the point.

"That was the smart thing to do." "Stupido, how could you be so dumb?" "Cosi sia, you deserved it." "E allora, no one is perfect." "Testa dura ("hardhead") you should have known better. Didn't we teach you anything?" "Oh, that's nice." One dialogue ended and immediately another began. Silent moments were rare at our table.

Then came the grand finale to every meal, the moment we dreaded most - the time to share the day's new learning. The mental imprint of those sessions still runs before me like a familiar film clip, vital and vivid.

Papa, at the head of the table, would push his chair back slightly, a gesture that signified the end of the eating and suggested that there would be a new activity. He would pour a small glass of red wine, light up a thin, potent Italian cigar, inhale deeply, exhale, then take stock of his family.

For some reason this always had a slightly unsettling effect on us as we stared back at Papa, waiting for him to say something. Every so often he would explain why he did this. He told us that if he didn't take time to look at us, we would soon be grown and he would have missed us. So he'd stare at us, one after the other.

Finally, his attention would settle upon one of us. "Felice," he would say to me, "tell me what you learned today."

"I learned that the population of Nepal is. . . ."

Silence.

It always amazed me, and reinforced my belief that Papa was a little crazy, that nothing I ever said was considered too trivial for him. First, he'd think about what was said as if the salvation of the world depended upon it.

"The population of Nepal. Hmmmmm. Well."

He would then look down the table at Mama, who would be ritualistically fixing her favorite fruit in a bit of leftover wine. "Mama, did you know that?"

Mama's responses were always astonishing, and seemed to lighten the otherwise reverential atmosphere. "Nepal," she'd say. "Nepal? Not only don't I know the population of Nepal, I don't know where in God's world it is!" Of course, this was only playing into Papa's hands.

"Felice," he'd say. "Get the atlas so we can show Mama where Nepal is." And the search began. The whole family went on a search for Nepal. This same experience was repeated until each family member had a turn. No dinner at our house ever ended without our having been enlightened by at least a half dozen such facts.

As children, we thought very little about these educational wonders, and even less about how we were being enriched. We coudln't have cared less. We were too impatient to have dinner end so we could join our less-educated friends in a rip-roaring game of kick the can.

In retrospect, after years of studying how people learn, I realize what a dynamic educational technique Papa was offering us, reinforcing the value of continual learning. Without being aware of it, our family was growing together, sharing experiences, and participating in one another's education. Papa was, without knowing it, giving us an education in the most real sense.

By looking at us, listening to us, respecting our opinions, affirming our value, giving us a sense of dignity, he was unquestionably our most influential teacher.

===

We need to stop assuming that everything our children learn at school is subversive. If we listen, really listen and look and THINK, and make our kids think, too, we might discover that our kids are really learning something cool. And if we continue to look closely and PAY ATTENTION, we might be able to detect it when the schools DO teach something dreadful.

Because, in some places, they already are.

The learning of, and comparison/contrast of, almost everything is wonderful. We know nothing if we only know one side. However, the deliberate indoctrination of almost everything is a dreadful disgraceful thing.

We will know the difference only if we actually pay attention. And before you go running to the school all outraged, make bloody sure you know what you're talking about.

Hitting the fan like no one else can. . .

Hitting the fan like no one else can. . .