Thursday, June 14, 2007

Where Are All The Fathers?

Sunday is Father's Day. My father died several years ago, a long, slow, drawn-out process that left my mother and my siblings and I drained and sad, and grateful when the final ending finally ended. I loved my father, with all his faults, and charms, and whimsicalities, and more faults, and understanding, and lack of understanding, and singing, and poetry, and callousness, and sensitivity, and many other adjectives, many contradicting the one before, and all true. With his older children, he was a fantastic father. With the younger siblings, his various illnesses had started to affect him, even before we realized it, and things in the house were different. Some of it wasn't his fault, and some of it was. In this way, he was no different than any of us.

Whatever may have crossed his mind from time to time, he never entertained the thought of leaving his family. I'm sure he was tempted to, as who isn't? but he had made a promise and he kept it. In my parents' home, promises meant something. On Father's Day, I will think of my father with love and a few head-shakings and a lot of forgiveness and smiling. And, a few things that I haven't forgiven yet.

It is entirely coincidental that our readings today in class were all about parenting, specifically, fathering. Our main reading was a Newsweek essay by psychologist Christopher N. Bacorn. The reading was prefaced by these statistics:

According to the National Fatherhood Initiative, an estimated 24.7 million children (36.3 percent) do not live with their biological fathers. About 40 percent of these children have not seen their fathers during the past year. A heartbreaking number of children have never, nor will they ever, see their fathers. Many do not know who their fathers are. Many of their mothers do not know, either.

"I had seen a hundred like him. He sat back on the couch, silently staring out the window, an unmistakable air of sullen anger about him. He was 15 and big for his age. His mother, a woman in her mid-30s, sat forward on the couch and, on the edge of tears, described the boy's heartbreaking descent into alcohol, gang membership, failing grades and violence. She was small, thin, worn out from frantic nights of worry and lost sleep waiting for him to come home. She had lost control of him, she admitted freely. Ever since his father had left, four years ago, she had had trouble with him. He had become more and more unmanageable, and then, recently, he had hurt someone in a fight. Charges had been filed, counseling recommended.

I listened to the mother's anguished story. "Are there any men in his life?" I asked. There was no one. She had no brothers, her father was dead and her ex-husband's father lived in another state. She looked up at me, her eyes hopeful. "Will you talk with him?" she asked. "Just speak with him about what he's doing. Maybe if it came from a professional. . . ." she added, her voice trailing off. "It couldn't hurt."

I did speak with him. Maybe it didn't hurt, but like most counseling with 15-year-old boys, it didn't seem to help either. He denied having any problems. Everyone else had them, but he didn't. After half an hour of futility, I gave up.

I have come to believe that most adolescent boys can't make use of professional counseling. What a boy can use, and all too often doesn't have, is the fellowship of men - at least one man who pays attention to him, who spends time with him, who admires him. A boy needs a man he can look up to. What he doesn't need is a shrink.

That episode, and others like it, set me thinking about children and their fathers. AS a nation, we are racked by youth violence, overrun by gangs, guns and drugs. The great majority of youthful offenders are male, most without fathers involved in their lives in any useful way. Many have never even met their fathers.

What's become of the fathers of these boys? Where are they? Well, I can tell you where they're not. They're not at PTA meetings or piano recitals. They're not teaching Sunday school. You won't find them in the pediatrician's office, holding a sick child. You won't even see them in juvenile court, standing next to Junior as he awaits sentencing for burglary or assault. You might see a few of them in the supermarket, but not many. You will see a lot of women in these places - mothers and grandmothers- but you won't see many fathers.

So, if they're not in these places, where are the fathers? They are in diners and taverns, drinking, conversing, playing pool with other men. They are on golf courses, tennis courts, in bowling alleys, fishing on lakes and rivers. They are working in their jobs, many from early morning to late at night. Some are home watching television, out mowing the lawn or tuning up the car. In short, they are everywhere, except in the company of their children.

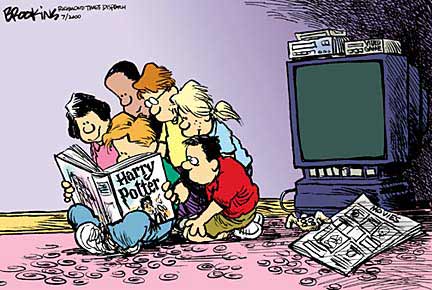

Of course, there are men who do spend time with children, men who are covering for all those absentee fathers. The Little League coaches, Boy Scout leaders, Big Brothers and schoolteachers who value contact with children, who are investing in the next generation, sharing time and teaching skills. And there are many fathers who are less visible but no less valuable, those who quietly help with homework, baths, laundry and grocery shopping. Fathers who read to their children, drive them to ballet lessons, who cheer at soccer games. Fathers who are on the job. These are the real men of America, the ones holding society together. Every one of them is worth a dozen investment bankers, a boardroom full of corporate executives and all of the lawmakers west of the Mississippi.

Poverty prevention: What would happen if the truant fathers of America began spending time with their children? It wouldn't eliminate world hunger, but it might save some families from sinking below the poverty line. It wouldn't bring peace to the Middle East, but it just might keep a few kids from trying to find a sense of belonging with their local street-corner gang. It might not defuse the population bomb, but it just might prevent a few teenage pregnancies.

If these fathers were to spend more time with their children, it just might have an effect on the future of marriage and divorce. Not only do many boys lack a sense of how a man should behave; many girls don't know, either, having little exposure themselves to healthy male-female relationships. With their fathers around, many young women might come to expect more than the myth that a man's chief purpose on earth is to impregnate them and then disappear. If that would happen, the next generation of absentee fathers might never come to pass.

Before her session ended, I tried to give this mother some hope. Maybe she could interest her son in a sport: how about basketball or soccer? Any positive experience involving men or other boys would expose her son to teamwork, cooperation, and friendly competition. But the boy was contemptuous of my suggestions. "Those things are for dorks," he sneered. He couldn't wait to leave. I looked at his mother. I could see the embarrassment and hopelessness in her face. "Let's go, Ma," he said, more as a command than a request. I walked her out through the waiting room, full of women and children, mostly boys, of all ages. Her son was already in the parking lot. I shook her hand. "Good luck, " I said. "Thank you," she replied, without conviction. As I watched her go, my heart, too, was filled with a measure of hopelessness. But anger was there too, anger at the fathers of these boys. Anger at fathers who walk away from their children, leaving them feeling confused, rejected, and full of suffering. What's to become of boys like this? What man will take an interest in them? I can think of only one kind - a judge."

I am really looking forward to next Thursday's essays!

I apologize if I seem a little off kilter tonight. This hasn't been an easy day, and I'm still a bit disoriented. But then, I've never had a student have a heart attack in my classroom before.

Hitting the fan like no one else can. . .

Hitting the fan like no one else can. . .